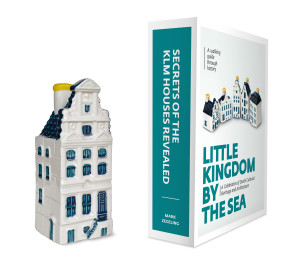

text from ‘Little Kingdom at the sea’ by Mark Zegeling

text from ‘Little Kingdom at the sea’ by Mark Zegeling

all about the ‘KLM Delft Blue Houses no. # 68’ Prinsengracht 969, Amsterdam

‘Amsterdam’s canal ring is a beautiful woman with foul breath.’

Nowadays, the water in Amsterdam’s canals is cleaner than ever. But four centuries ago, right after the construction of the canal ring, people protested about the filthy water. The stench of rotten eggs caused the inhabitants of the chic canal houses to hold their breath. In the Golden Age century, the smell of success could only be experienced indoors, behind Amsterdam’s beautiful gables, because the pungent odour on the streets was simply disgusting.

It was awful in summer especially, when the water was low. The canals were like open sewers. Domestic dwellers, as well as businesses, simply threw all their waste into the water. Filth floated everywhere: from human faeces and household garbage to manure and rotting meat.

STIFLING SULPHUR FUMES

In 1666, the Frenchman Pierre Le Jolle wrote in a travel guide about Amsterdam that the city ‘can be smelled from kilometres away.’ That’s why he dedicated his book to ‘the poorly educated, filthy, lazy, unhygienic and dumb gentlemen mud workers and cleaners of the Amsterdam canals’. The suffocating sulfur fumes of waste became an ever-increasing problem. By the end of the 17th century, some 200,000 people lived in Amsterdam. It was the third-largest city in the world, only London and Paris had more inhabitants. Drinking water had to be brought in by ship, as the dirty and salty water in the canals was not potable and caused disease.

PIGS ADDICTED TO ALCOHOL

At the IJ side, the Prinsengracht was closed off by the Eenhoorn lock and at the other end, it flowed into the river Amstel. In 1690, near this crossing of waterways, a stylish house with a fine neck gable was built at Prinsengracht 969. The top is crowned with a sandstone pediment. Stone scrolls with a flower motif support the neck.

Amsterdam Water Level adapted as European Standard

Water levels in Europe are fixed according to a standard that originated in Amsterdam. Until the 17th century, the water level in the city was determined by the high and low tide. However, after the installation of locks, the lockkeepers could influence the quantity and quality of the water in the canal system. Therefore, in 1684, Mayor Joannes Hudde fixed the mean water level. All locks were fitted with a white marble stone with a groove at ‘negen voet five duijm’ (9 feet, 5 thumbs = 2,68 m) below ‘Zeedijks Hooghte’ the level of the sea dike. That way, the lockkeeper knew exactly at which water level the gates needed to be opened and closed. This standardization of the water level is called N.A.P. (Normaal Amsterdams Peil) and is in use all over Europe. Of the original eight marble stones spread across the city in 1684 to measure water levels, only the Hudde Stone in the Eenhoorn lock, at the beginning of the Prinsengracht, is left.

The mansion at Prinsengracht 969 may look respectable, but as soon as the occupants step outside, they inhaled the foul odours of pigs’ manure and urine. There was a jenever distillery close by and instead of dumping the waste swill into the canal, it was used to feed his pigs. Since this residue of the production process contained alcohol, the poor animals not only became addicted but fattened sooner too. The distiller didn’t mind that the meat was of lower quality; the important thing was that his jenever tasted excellent. Nobody particularly bothered that he threw faeces, offal and old hay into the Prinsengracht.

ANTIQUITY DISCOVERED

In the 18th century, the mansion at Prinsengracht 969 underwent a significant renovation, during which time the façade was decorated in the Dutch classical style. This building style was a result of new interest in Antiquity, after the discovery of the Italian cities of Herculaneum in 1709 and Pompeii in 1748, destroyed centuries before by natural disaster. Midway through the 18th century, the property at Prinsengracht 969 installed distinguished elevated entrance steps and a door framed by Roman engaged pilasters. The beautifully crafted cutting frame above the door is representative of the more sober and classical Louis XVI style.

Photo back (in construction)

The back of Prinsengracht 969 has an extraordinary feature. Since it was always shaded from the sun, the location remained cool. The first inhabitants used this to their advantage by attaching a small extension that functioned as a 17th-century fridge.

It was also likely that the pediment disappeared during this period, to emphasize the symmetry of the neck gable.

‘THE MOST UNHEALTHY PLACE IN THE WORLD’

The occupants of Prinsengracht 969 would, no doubt, often been affected by the stench in their street. By the end of the 17th century, there were around twenty breweries, twenty confectioners and as many as seventy dyers in the immediate vicinity. They all dumped their waste directly into the Prinsengracht. Tourists and other visitors could not adjust to the stench and Amsterdam was known as the ‘beautiful maiden with foul breath.’ Fortunately, an increasing number of businesses on the canal were forced to move to the edge of the city. However, the quality of the canal water remained bad. A century later, in 1838, a German tourist writes: ‘The stranger who surveys this city cloaked in a blue mist and breathes in her unpleasant odours, would declare her the most unhealthy place in the world.’

DEADLY CHOLERA EPIDEMIC

The Prinsengracht formed the outside ring of the canal system and with that, the longest. It also meant it took longer to refresh the water. For centuries, draining the canals was seen as the best solution to the stench nuisance. Seventy canals meet their fate in this way, but because the Prinsengracht was important for the transport of goods to the many warehouses, draining of the canal was never a serious option. This did mean, however, that during an outbreak of cholera, most victims fell in the tightly populated and poor Jordaan district, as people there continued to drink the foul canal water. Amsterdam was hit three times by cholera epidemics between 1832 and 1866. The lack of clean drinking water and an efficient sewer system contributed to the high death toll. Four years after the last 1870 epidemic, the city started a large-scale sewer construction project.

THE CANALS ARE CLEANED UP

In the meantime, another huge project was underway, namely the digging of the North Sea Canal from Amsterdam to IJmuiden. The work was carried out by order of King William III and would connect Amsterdam with the North Sea via the IJ. In this way, the Zuiderzee (now IJsselmeer) to the east of Amsterdam, became less important as a trade route. The construction of the Orange Locks (Oranjesluizen) even meant that Amsterdam could now be closed off completely. Since 1878, the pumping station Zeeburg pumps clean water from the Zuiderzee into and through Amsterdam’s canals. The twelve locks are closed each night at ten p.m. and not opened again until the following morning at 5 a.m. In summer, the canals are rinsed four times a week and twice in winter. Each time, 600,000 m3 of clean water flows through the city. The process of connecting the canal houses to the new sewer system continued relentlessly well into the twentieth century and in 1987 the last property was connected to the network. However, there are around eight hundred canal boats in the centre of Amsterdam and a number still dump toilets and other wastewater into the canal. The city council aims to have all canal boats connected to the sewers by 2016.

SHORT STAY IN A REAL KLM HOUSE

Little is known about the history of the house at Prinsengracht 969, but you’re invited to explore it’s present. Today, Prinsengracht 969 is a charming and romantic Bed & Breakfast, which can lodge up to two guests.